Deliberations are underway in the trial offormer Uvalde schools police officer Adrian Gonzaleson Wednesday after prosecutors and defense lawyers delivered their closing arguments.

Before jurors were sent to deliberate, District Attorney Christina Mitchell gave an impassioned plea, saying, "I know this case is difficult, and it has been difficult. But we cannot continue to let children die in vain."

"What happened to Uvalde on May 24 can happen anywhere, at any time," she said. "If it's going to happen, and if we have laws mandating what the responsibility of a law enforcement peace officer is for a school district, then we better be ready to back it up."

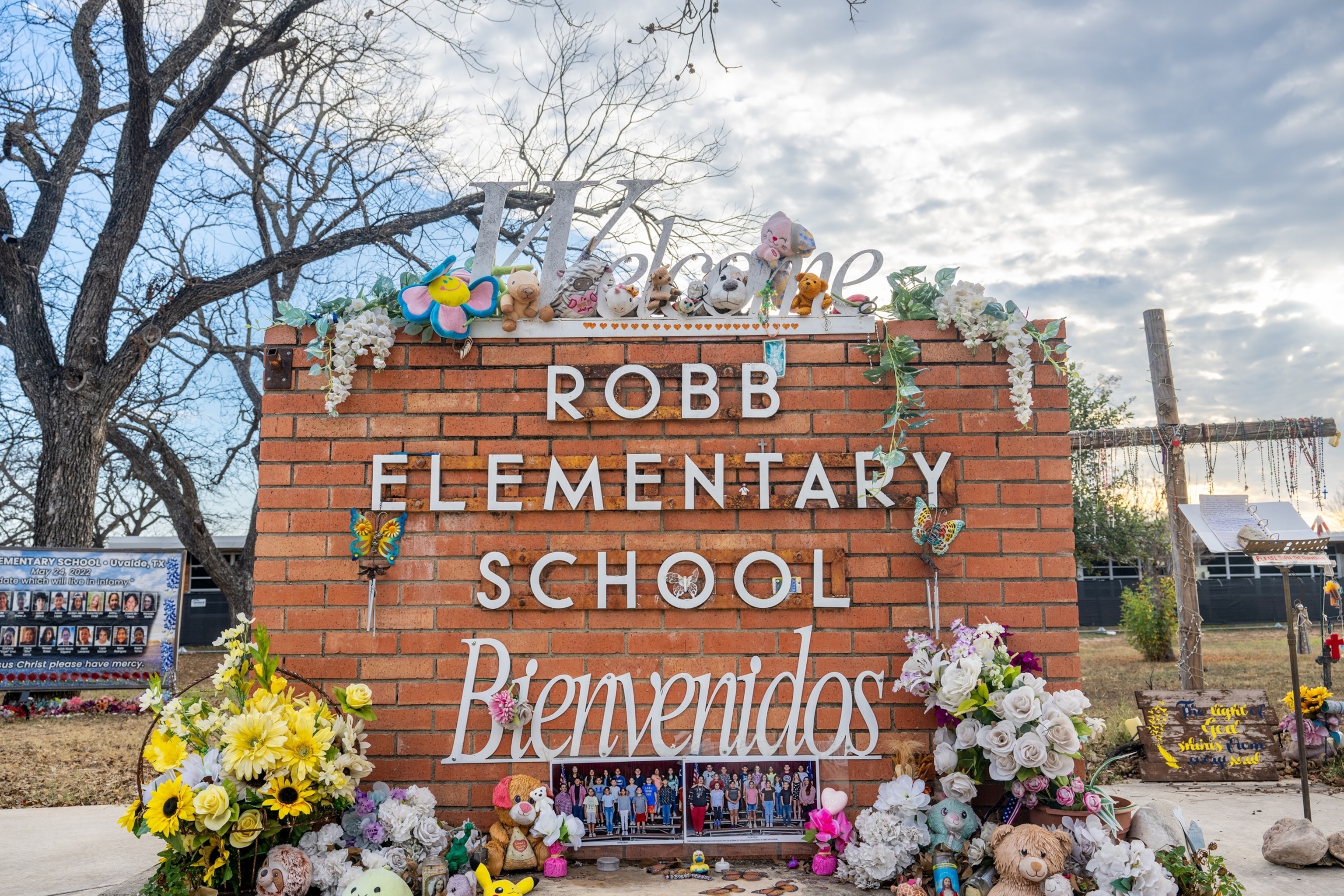

At issue is whether Gonzales -- one of the first officers to arrive at Robb Elementary on May 24, 2022 -- ignored his training and endangered dozens of students when he responded to the shooting, which became one of the worst mass shootings in U.S. history.

Uvalde school shooting timeline: Prosecutors say officers arrived before gunman entered building

Nineteen students and two teachers died, with police officers waiting77 minutesto confront the gunman. While the shooting response has been the subject of hearings and investigations, the case against Gonzales marks the first criminal trial related to the shooting and the delayed police response.

Prosecution's closing argument

The jury has an opportunity to "set the bar" for how officers should respond to school shootings, prosecutor Bill Turner said on Wednesday.

"If it's appropriate to stand outside hearing [hundreds of] shots while children are being slaughtered, that is your decision to tell the state of Texas," Turner said.

While teachers and students were sheltering in their classrooms -- doing exactly what their training taught them to do in an active shooter scenario -- the police officer trained to help them failed to act, Turner said. Turner argued that each gunshot fired at Robb Elementary was "notice to Adrian Gonzalez to advance toward the gunfire," but he failed to follow his training and act in the crucial first minutes of the shooting.

Uvalde officer Gonzales may have suffered from 'tunnel vision,' defense witness says

"If you have a duty to act, you can't stand by while the child is in imminent danger," Turner said.

Turner pointed jurors to the testimony ofteaching aide Melodye Flores, a key prosecution witness who said she pleaded with Gonzales to intervene. Turner argued that the warning from Flores and the clear sound of gunfire should have triggered Gonzales to act.

"The training is, you hear shots, you go to the gunfire. He heard shots, and Melodye Flores was pointing where to go to the gunfire. There's nothing complicated about that," Turner said.

Defense's closing argument

Gonzales "drove into danger" to stop the shooting, defense attorney Nico LaHood told jurors.

LaHood argued that Gonzales did more than many of the officers who responded that day but is now being unfairly penalized. He directly compared Gonzales' actions to Daniel Coronado, a former Uvalde police sergeant, who responded within 30 seconds of Gonzales.

"Adrian drove into danger. Sarge stayed away at the perimeter. Adrian, no line of sight. Sarge, same side as the shooter. Adrian alone. Coronado has backup," LaHood argued.

Convicting Gonzales will send a clear message to officers who respond to this country's next mass shooting, defense attorney Jason Goss said.

"What you tell police officers is, 'Don't go in. Don't react. Don't respond,'" Goss warned jurors. "We cannot have law enforcement feel that way."

Goss argued that prosecutors tried to "massage the facts" of the case and"twist them all into a pretzel" to argue Gonzales failed to act. According to Goss, Gonzales did the best he could with the information he had when he arrived at Robb Elementary. While other officers arrived within the same timeframe, only Gonzales is being penalized for attempting to take action that day, he argued.

Goss attempted to empathize with the jurors and the families of victims, arguing he understood the desire for criminal accountability. But he reminded jurors, "The monster who hurt those kids is dead."

But convicting Gonzales, Goss argued, would do "an injustice" for the victims of the shooting.

"You do not honor their memory by doing an injustice in their name," he said.

What is he charged with?

Gonzales was charged with 29 felony counts of abandoning/endangering children -- one count for each of the 19 students who died in the shooting and the 10 children who survived in classroom 112.

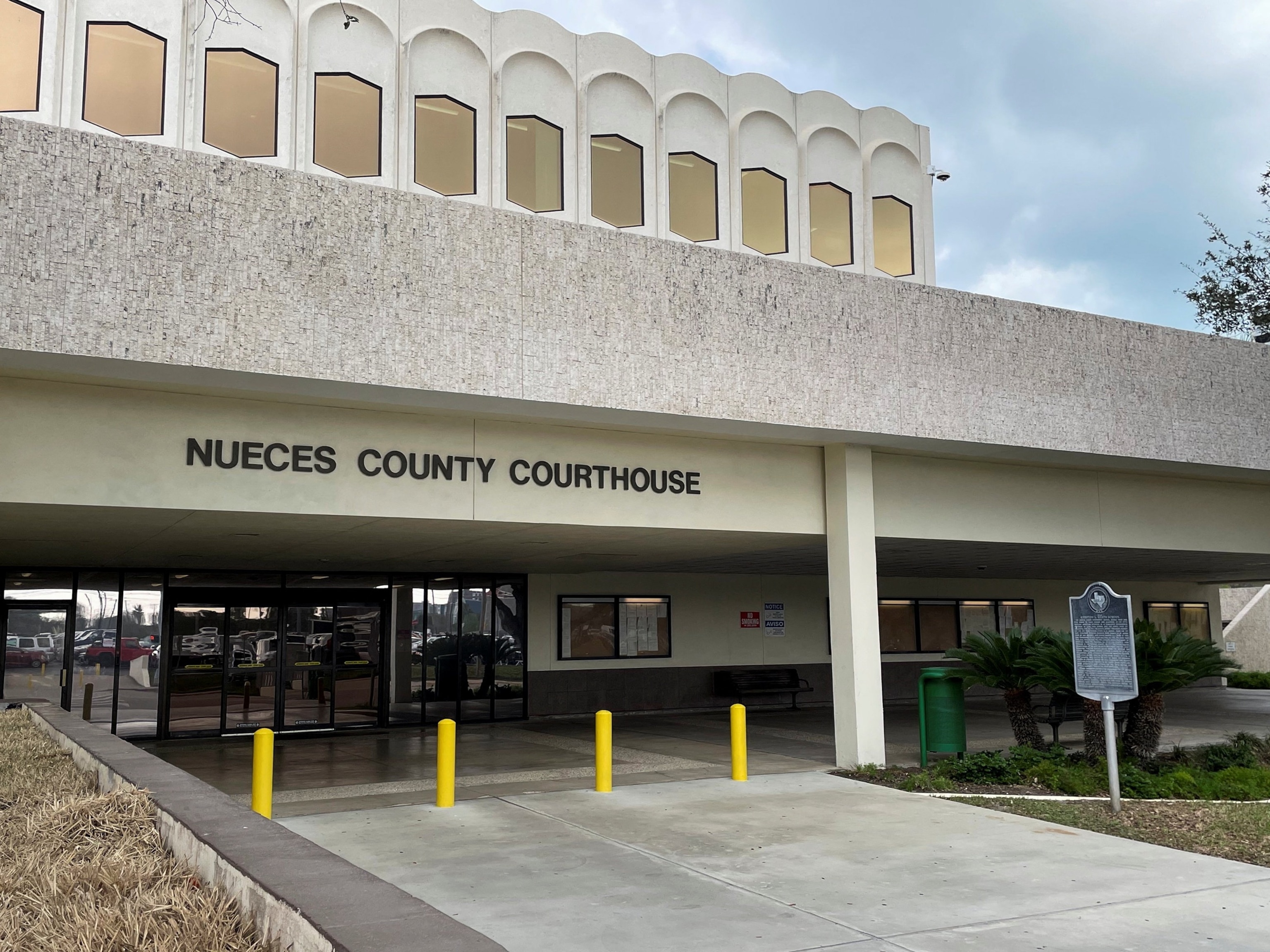

Each count carries a maximum penalty of two years in prison, and Gonzales could spend the rest of his life in prison if he is convicted. While juries in Texas sometimes determine criminal sentences, Gonzales has opted to be sentenced byJudge Sid Harleif he is convicted.

What happened to the police chief's case?

Along with Gonzales, prosecutors also charged former Uvalde schools Police Chief Pete Arredondo, who was the scene commander during the Robb shooting. His case has been indefinitely delayed due to a pending civil lawsuit involving the tactical unit that ultimately breached the classroom and killed the shooter.

Are there any comparable cases?

According to Phil Stinson -- a professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio who maintains a database of police officers who have been arrested -- the case against Gonzales is uncommon but not unprecedented.

Prosecutors in Florida attempted to similarly charge a law enforcement officer for his response to the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Seventeen were killed when a gunman opened fire that day, Feb. 14, 2018, in Parkland.

A jury in 2023acquitted Scot Peterson, the former Broward County sheriff's deputy, after he was charged with child neglect and culpable negligence for his alleged inaction following the shooting.